Fear in paddlesport

Versions of this article also appeared in "The Paddler", the Glenmore Lodge blog and the "Coaching Adventure Sports" book.

I'll let you into a secret.

I'm often scared when I'm boating. As a paddler

I'm scared I'm going to stop improving as I get

older; as a coach I'm scared I'm not going to give

my learners the awesome day that they deserve.

We'll come back to that at the end. Now for a bit

about brains...

Two brains for the price of one!

The brains of many animals have some bits in common.

Those bits are involved in things like motivation, emotion, learning and memory. We'll

call this the limbic brain. Apes (including us) and some other animals have some extra

bits which are involved in thinking. That's the cognitive bit of brain you're using to read,

interpret and understand this article right now.

One bit of the limbic brain is involved in reacting to threats. It's directly wired to our eyes

and ears and can trigger a load of responses in the body. Typically fight, flight or play

dead. It reacts in about 1/60th second. It's not until another 1/60th of a second later that

your cognitive brain catches up, becomes aware of what's already happened to your

body, and this is what we call being afraid.

That may sound like a load of neuroscience waffle, but just think about that last

sentence;

Your cognitive brain isn't involved in triggering your fear response.

Being scared isn't a thinking choice – you can't think yourself out of being afraid.

Your body is probably already doing stuff before your cognitive brain (i.e. YOU!) are

even aware of the threat.

This made a load of sense 2 million years ago when our ancestors were pottering around

the African plains. By the time your cognitive brain has worked out that the rustle you

heard in the savannah might be due to that cackle of hyenas you saw yesterday, you're

already their lunch. Much better to have a fast reacting, easily triggered limbic system

that has you climbing the nearest tree before you know why you're doing it. The odd

false alarm just means you end up occasionally climbing trees for no good reason. Failing

to trigger just once means you're hyena food!

A bit more about the limbic brain

The limbic brain is born with some triggers – babies are afraid of toy snakes, even in

countries where there are no snakes.

The limbic brain is incredibly good a learning to be afraid of new things. You only need

one bad experience and the limbic brain can learn a new trigger, and that learning can

last a lifetime.

It doesn't even have to be a bad experience that happened to you. You can learn to beafraid of something from someone else's experience.

The limbic brain doesn't choose the trigger in a rational way. If you have a bad

experience on a river your limbic brain might choose to fear; all watersports, kayaking,

green kayaks, holes, that particular drop or paddling with your mate Reg. There's no

logic to it, because the limbic brain doesn't do logic – that's what your cognitive brain

does.

If you were going to invent a sport to trigger our primal fears it might look quite like

white water kayaking. Noise, splashing, power, unpredictability, drowning, entrapment.

Maybe it needs a few snakes wriggling around inside your boat to make it perfect.

That's also why whitewater is so much fun! If I gently push the buttons of my limbic

brain, then a fraction of a second later my cognitive brain gets to experience all the

excitement and stoke of piloting a crazy little boat down an ever changing roller-coaster

of moving water. If something fully triggers my limbic brain the excitement turns to fear,

terror or an out and out emotional meltdown!

|

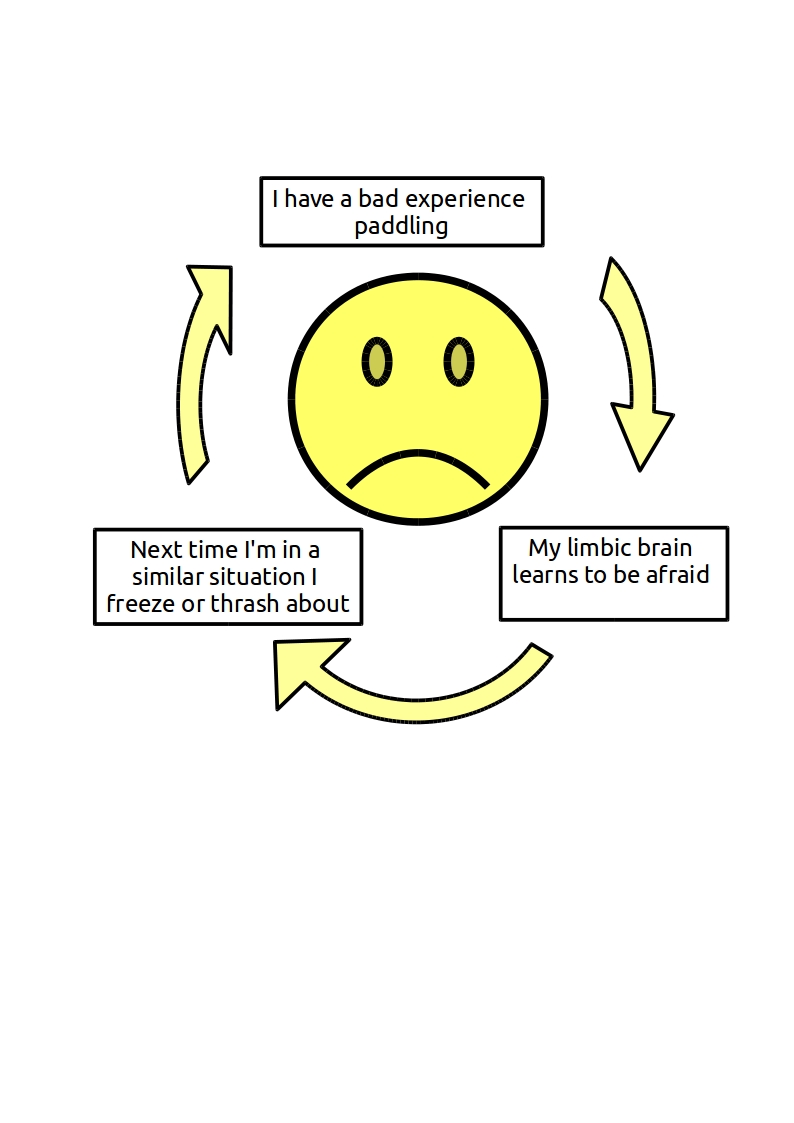

It gets worse. If my limbic fear response is

fully triggered, I'll tend to either freeze or

thrash around ineffectually (that's what

play dead, fight or flight look like in a

kayak!) The stuff that worked on the

African savannah really doesn't work on a

river. I have a bad experience and that just

reinforces the fear response (remember

the limbic brain is really good at learning

to be afraid of stuff).

So I get locked into a feedback cycle where

boating makes me afraid, being afraid

makes me rubbish at boating, I get nailed and that makes me even more afraid next

time! |

|

Remember, it's not a cognitive thing. Knowing that we've set safety, knowing that it's a

low-consequence rapid doesn't help because the limbic brain doesn't respond to reason.

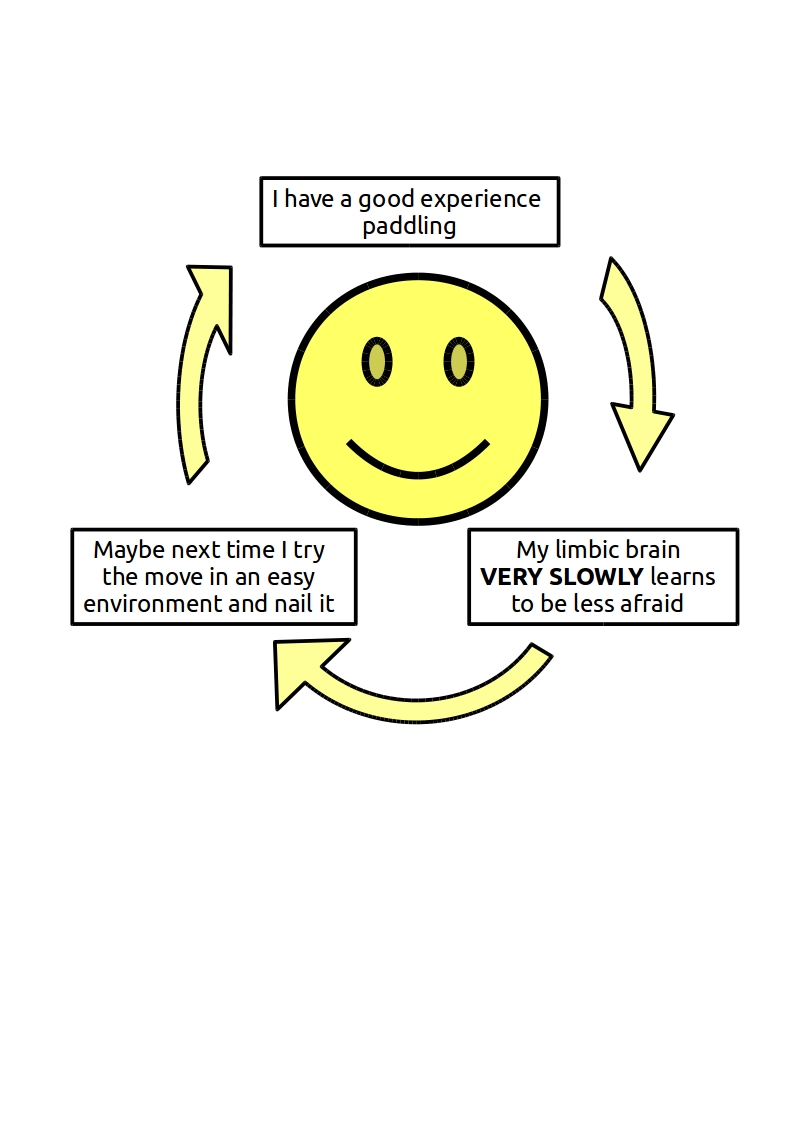

The long slow path to success.

|

It is possible to teach your limbic brain that paddling is

OK. You can't reason with your limbic brain, but you

can teach it.

You do that by being exposed to the fear trigger, but

having a good outcome. If the fear is of swimming

rapids, then go and swim some safe rapids. It seems

that the more scared you can be and still get a good

outcome the more effective this method can be.

Of course that doesn't work if the fear is of a particular

move or a particular rapid that requires you to drive

your boat. At this point being really afraid will mess upyour performance and put you right back into the bad feedback cycle.

|

Here we need to

find a way to make it easier and get some success; can we find a similar move in an easier

environment? Can we break the move down and practice some elements of it? Will

getting fitter help? Is the underlying problem to do with fear at all, or is it simply a lack

of technical ability to make the move?

Eventually if I keep getting success and I gradually increase the difficulty level, I can

slowly teach my limbic brain that it's OK. Of course it could only take one failure to put

me back to square one. If you're sitting in the eddy at the top of a rapid, unable to

swallow, talk or think, it's probably a sign that you shouldn't be paddling it.

Some quick bodges

These probably won't fix the fear in the long term, but they might allow you to get down a rapid!

Visualise – shut your eyes and go through a successful run inside your head. It'll help

your cognitive brain sequence the moves and it might just kid your limbic brain into not

triggering.

Breathe – slowly and deeply. It might do some clever physiological stuff to your nervous

system. It will certainly give your cognitive brain a bit of space.

Mindfulness – Listening to your body, being aware of how scared you are and how it's

affecting you. Don't analyse it, just be aware of it.

Focus – under pressure the cognitive brain can focus on the wrong cues. A bit like

visualising, planning the key moves of a rapid and having a cue for what's going to make

you do the right things at the right time can help.

Don't focus – for other people under pressure, they try to pay attention to too many

cues. The cognitive brain tries to micro-manage every movement. The movement loses

fluidity. Distracting the cognitive brain and letting the limbic brain drive is what's

needed.

So to take it back to the start, I'm often scared when I'm boating, but nowadays it's

usually cognitive. Being scared of getting worse at boating makes me try new stuff,

paddle more and train better. Being scared of not giving my learners a good day makes

me get feedback on my coaching and try to improve it. I think that's a good rational

thing.

On the occasions I find my limbic fear kicking in, I usually recognise it happening. If I can't

fix it, I usually get out and walk. The rapid will be there for another day.

If you want to read more, from a paddler's perspective I really recommend "Whitewater Philosophy" by Doug Ammons.

For the neuroscience perspective, "The Emotional Brain" by Joseph LeDoux is excellent.

If you'd prefer a popular science book, "Nerve: Poise Under Pressure" by Taylor Clark is well worth a look.